All you need to know is that this is an encore of Marlin’s Musings, which first appeared on this page three or more years ago. My advice: Even if you’ve read previously, read on … it’s an extremely humorous story from radio’s early days:

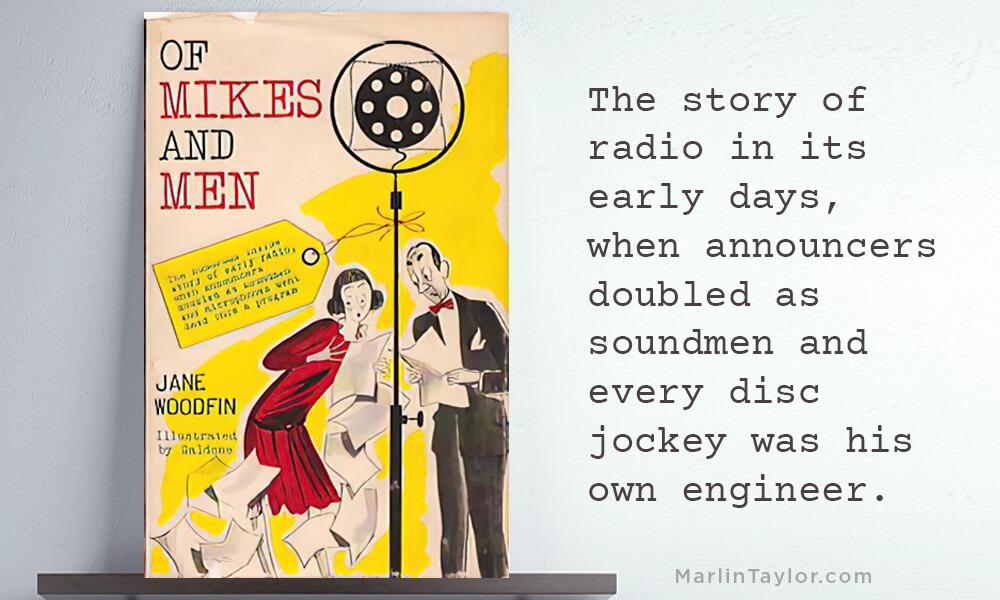

This is a book I first read several years ago, having been loaned to me by my longtime radio industry friend, Ken Mellgren.

Radio history has always been of interest, especially after my first radio-related job in the mid-1950s was with a station still operating with much of the studio and transmitting equipment acquired in 1936 … although it had at least advanced to better microphones and turntables that played LP’s and 45 RPM discs.

The ad said:

Wanted, experienced continuity writer. Female. Apply Station KUKU, between 9 and 11 A. M.

Those are the first words you read when you open this book and begin to read what’s classified as a novel, but considered to be 99% real stories and facts about the writer’s experiences while working for an historic Portland, Oregon, radio station, KEX … which she calls KUKU in the book. Published in 1951 by one Jane Woodfin, an ancestral family name used as an alias by Evelyn Sibley Lampman, who became an acclaimed author of numerous children’s and young adult novels.

Timeline: 1930, just months after the Wall Street Crash in the fall of 1929 and the beginning of the Depression.

I’ve chosen a couple of snippets to share with you … the first showing what radio broadcasting could be like in its early days, the second you could almost envision happening today some 90 years later. Read on…

The writer begins by explaining that while she had no idea what was “continuity” — which commonly is called copy, whether it be a commercial for an advertiser or a program introduction — she had a desire to become a writer, plus it was the only listing under Help Wanted in the morning newspaper.

She, along with many other women, showed up … and she is the one eventually hired … because the manager liked the sound of her voice compared to the rest of the applicants, not based on her writing skills.

At that point, she’d learn writing continuity was only half of the job; the other was hosting a half-hour morning cooking show! For a young woman who knew little about cooking, it was her job searching out recipes and organizing them for airing … with her as the broadcaster. And, the first broadcast would be the following morning! For all of this, she’d be paid the magnanimous sum of $25.00 per week.

After many hours spent getting a cookbook and writing a script, she showed up at the station the following morning at the appointed time:

A small glassed-in cubicle on one side of the front door was reserved for the manager, and on the opposite side of the lobby were doors marked, respectively, “Ladies” and “Gents” and a longer office containing empty desks, typewriters, chairs, and filing cabinets. Windows and a glass door on the farther side of the reception room looked into the single studio, and it in turn was flanked by the control room, a mysterious affair filled with batteries and switches, a turntable for playing records, and an electric oven for storing microphones overnight. This oven was one of the most important pieces of equipment, since the fine crystals of carbon which carried the voice waves had a tendency to collect moisture and pack down solid during the day. Heat loosened them once more, and our programs, consequently, were always clearer in the early morning than late at night. Jack Woolen was at his desk glowering at the morning newspaper and wondering which one of the advertisers therein he could approach with a schedule card and a request to buy time on the air. He put down the paper to glower at me instead.

“Oh, it’s you,” he grunted by way of salutation. “Come on. I’ll have to introduce you to the announcer.” The announcer was a tall, thin individual with sparse, greasy black hair carefully distributed to best advantage, and with a supercilious manner. Those were the days when announcers were important persons, and no one knew it better than they.

“This is Roland Bean,” mumbled Mr. Woolen. “He’ll put you on and give you a couple of records to play.”

“Records!” I gasped.

“Can’t have a woman gabbing for a whole half hour without a break. Listeners wouldn’t stand for it. One phonograph record in the first fifteen minutes, another in the second. I’ll be listening. You better be good.”

He left me with Mr. Bean.

” ‘Doll Dance’ and ‘When the Red Red Robin Comes Bob Bob Bobbin’ Along,’ ” announced Mr. Bean. He always spoke as though he were delivering a commercial message for a zealous sponsor. “You announce them. I play them from the booth. Write them down, because I won’t be in there to remind you if you forget.”

Rightly assuming that these were the musical selections which would brighten my culinary chatter, I wrote the titles hastily on the top of my script.

“You ever worked a mike before?” he demanded. I hesitated, but this was no time to bluff. This time I had to have help. I shook my head, and he nodded with satisfaction. “I thought not. Jack couldn’t hire anybody with experience for what he’s willing to pay. Come on and I’ll show you.”

“I’m getting a good salary,” I objected indignantly as I followed him into the studio. ”Twenty-five dollars a week!”

“The Better Homes Girl we had before The Crash got that for doing this one program and nothing else. She wasn’t on full time, only for this one show. And you’ll be writing continuity, too, Jack says.”

“That’s right.”

“We used to pay our writers thirty-five and forty dollars a week,” he said triumphantly. “Besides, it was all in cash. Now, you sit here at this table.”

I sat at the table. Facing me was the round disk I had encountered briefly the day before, but somehow it had changed. The blank mesh face had suddenly assumed an expression. Two of the decorative holes in the frame I singled out as eyes, and those eyes were staring at me balefully.

“This is a microphone,” said Mr. Bean witheringly. “You talk straight into it, like this. Don’t get your face off to an angle, or it will whistle. If you see me pounding on the glass of the control room, that means it’s gone dead on you. Then you pick it up and shake it, like this.”

“What does that do?”

“Jolts loose the carbon crystals. This is a carbon mike. Got to keep them loose. Be sure to keep your eye on me. They’ll probably pack down a couple of times during the show. And remember to keep looking straight at the mike.”

How I could simultaneously watch Mr. Bean through the window and keep looking straight at the mike I couldn’t imagine, but I nodded meekly. I was too much in awe of everything to question his obvious intention of leaving me alone. As a matter of fact, it was necessary that he do so. The early announcers were, in most cases, their own technicians. Many of them had regular operator’s licenses, and it was only an occasional program which was announced from the studio. Generally it was done from the control room where the announcer could flip a switch to turn on the voice microphone and another to pick up the music of a record. Moreover, when anyone was talking, he was required to keep his hand on a little dial which regulated the volume of tone coming over the air.

“You want the same introduction?” he continued. “You going to be Nancy Lee, the Better Homes Girl of the Golden West Network?”

“I think so.”

“I’ll introduce you as that. If Jack had wanted a change, he’d have said so. There’s the clock up there. Keep watching it so you’ll know when to sign off. When you see me jab like this, it’s time to start talking.”

With that he left me and the round accusing eyes of the microphone alone, and I discovered I was frightened. My hands, when I attempted to unfold my script, were sticky with dampness. My stomach had somehow moved up from its accustomed position and was lodged in my throat. It interfered with my breathing. If my legs had not been so weak, I would have run from that room, gladly throwing away all the glamour of radio and my chance at a job and a twenty-five-dollar pay check. But my legs would not carry me.

I sat on, watching the second hand of the studio clock gallop around and the minute hand race to overtake it. Always my eyes came back to that evil circle facing me on the table. Four minutes. Three minutes. I counted the soiled folds of monk’s cloth which draped the room from ceiling to floor. Twenty-two folds across––no, twenty-three if you counted the big bunch in the corner, but maybe half of that should he counted on the other wall. The microphone was still there, jeering at me. Two minutes. One minute.

Desperately I cleared my throat and my voice croaked back at me. Then I was aware that Mr. Bean was pounding on the control-room window, his finger jabbing at me accusingly. I raised my script, took a deep breath, and opened my mouth.

“Good morning, girls,” I quavered. “How about surprising the family with a lovely tutti-frutti cake for dinner tonight? I have the recipe right here, and if you’ll all run and get your pencils and papers, we’ll start right in on it. I’ll wait while you sharpen your pencils.”

At the first break for a musical number Mr. Bean appeared beside me with criticism and advice.

“You’re not good,” he said, “but maybe I’ve heard worse somewhere. Keep your eye on me. You lost a whole minute with a dead mike.”

If I expected the second half of the program to go more easily than the first, I was disappointed.

Skipping ahead a few pages, Miss Woodfin had managed to get through her first full week as the new host of the daily women’s cooking program and get command of her duties as the station’s continuity writer, turning out several commercial announcements and programming scripts. Then it was time to collect her first remuneration:

The first pay day at KUKU was one which will always stand out in my memory. I had ducked downstairs on the chance I could talk the restaurant operator into trusting me for a cup of coffee, and when I returned, Miss Millikin, the combination bookkeeper, stenographer and receptionist had delivered our checks.

Mine was fluttering in my typewriter, but the desk top was practically hidden by a miscellany of unrelated articles which had no place there. On first glance these included twenty loaves of bread, a glass bowl in which swam two goldfish, and a gigantic carton labeled “Fish Food,” certainly enough to satisfy every piscatorial denizen of the Columbia River. There were also several unidentified parcels wrapped in brown paper. As I reached my desk, Miss Millikin came hurrying over.

“Here’s your inventory,” she said. “Please sign your name for a receipt.”

But I had already seen the figure on the check. “just a minute,” I interrupted quickly. “There’s been a mistake. I’m to receive twenty-five dollars a week. This check is for only ten dollars.”

“You surely didn’t think you’d get it all in cash?” she demanded in surprise. “You have fifteen dollars’ worth of merchandise on your desk. That makes up the difference.”

“But I don’t want merchandise. I want the money.”

We all had the full amount of our checks in cash before The Crash,” she said dreamily. “But, of course, that isn’t possible now. The station has to take part of the amount our clients owe for radio time in merchandise. Naturally, these portions have to be passed over to our employees. The head office wouldn’t accept them. But Mr. Woolen is very fair about it. If you can find a store which will let you redeem the merchandise for cash, you’re free to do so. Personally, I’ve never been so lucky.”

“What’s in these other packages?” I demanded, jabbing at one with my finger. I was rewarded with a metallic clank.

“That would be nails and bolts,” she told me. “Ten of them. From Henderson’s Hardware. You should remember. You write their copy. And the envelope contains a dollar-and-a-half’s worth of tickets from the amusement park. They’re good for Joy Rides. But be careful of the bulgy package. There’s two bottles of Patton Brothers Hair Renew in there, and they’re breakable. There’s also one of their Magic Massage Brushes to stimulate sluggish scalps.”

I stared at the motley collection in horror as Miss Millikin thrust a pencil in my weak fingers.

“It’s all here on this slip,” she said. “There’s a carbon for you. Everything is listed according to its retail price. You’ll find it quite correct. Fifteen dollars’ worth of merchandise. Please sign.”

I signed. There was nothing else to do. Outside of the manner in which I was to receive my pay and the recipes which I resented copying each night and delivering each morning, I was enjoying my job. I was learning to write continuity in the best possible way by doing it.

At this point, we are only on page 21 of Of Mikes and Men …with 225 pages remaining. The book has been described as a “humorous inside story of radio in its diaper days … based on incidents from the days when radio was local and real.”

As a side story, I can tell you that at that point, the station was less than four years old. The original builder of the station had run out of funds and one month before the Crash, it and its sister stations had changed ownership … leaving them, at least temporarily, in survival mode.

If you have an interest in reading this story, at last check there were a few pre-owned copies available via Amazon.

P. S. – I’m always interested in hearing from you, the reader. Any comments or thoughts regarding what I’ve shared here or in any other Musings? If so, let me hear from you: marlin@marlintaylor.com – Thanks!

Carbon microphone photos courtesy of the Ken Mellgren Collection and Brian Belanger, curator of the National Capital Radio & Television Museum.

Of Mikes and Men – © 1951 by Jane Woodfin – Published by McGraw-Hill Book Company