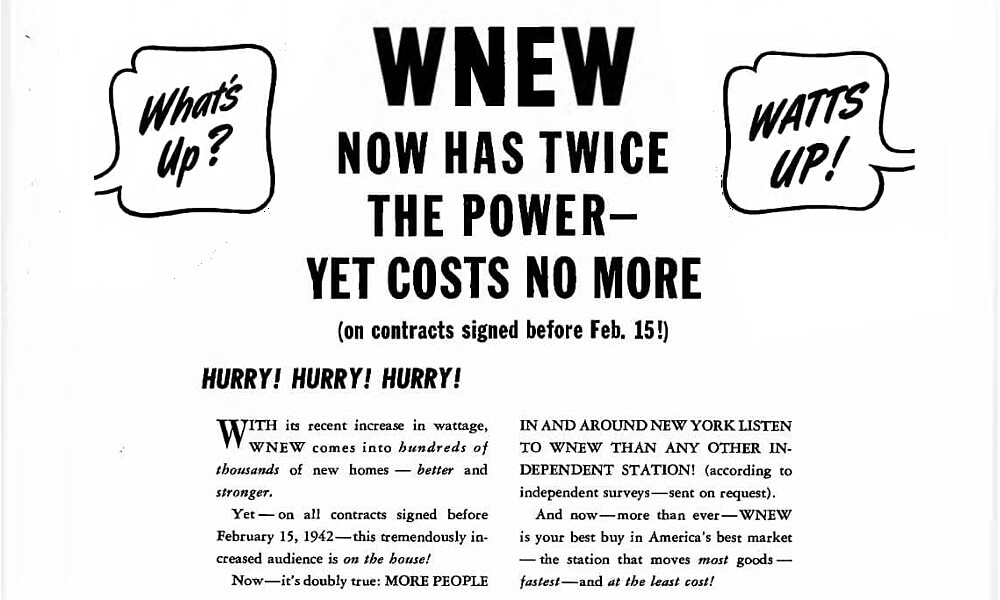

Now, with 10,000 watts of power — which, in the big picture, is relatively equal to 50,000 watts — and located down at 11-3-0 … the Judis dynamo operation is ready to really shine and show the world what great “listener-focused” radio is!

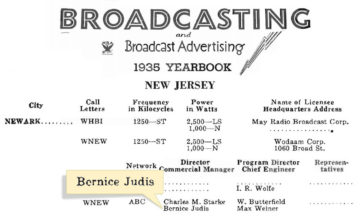

Picking up where we left off in Chapter One, here’s the next section of the WNEW and Bernice Judis story as told by “insider” Richard Pack in a 1983 article which was published in the long-defunct broadcast industry publication, Television-Radio Age:

Picking up where we left off in Chapter One, here’s the next section of the WNEW and Bernice Judis story as told by “insider” Richard Pack in a 1983 article which was published in the long-defunct broadcast industry publication, Television-Radio Age:

Formula evolved …

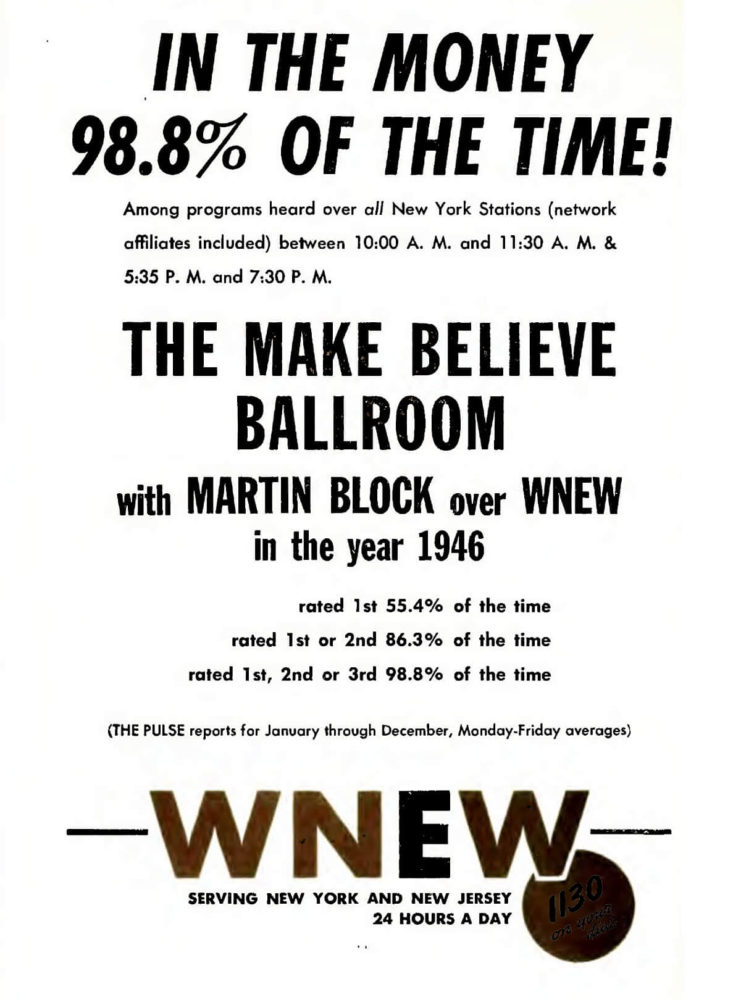

It didn’t happen overnight. The formula evolved, first from Martin Block and his Make Believe Ballroom, daily from 10 to 11:30 a.m. and 5:30 to 7:30 p.m. Then came other disc jockeys in different time slots, each for a couple of hours, six days a week. Across the board.

Strip programming, large chunks of time, the same kind of programs — block programming with a small “b” was the basic of the music-and-news format. Again, the idea now seems so simple, so obvious. But the networks were programmed — except for the daytime serials — on a checkerboard pattern of shows, like TV, with different programs each night of the week.

Judis built WNEW around what she once described as a “water faucet” base: listeners would know that whenever they tuned in to WNEW, they would get the same kind of programming — personality disc jockeys, not for 15 minutes or a half hour, but for two or three hours. It built habit and audience.

In those early years, records were not the only major program source. There were live shows, too. Young stars like Frank Sinatra and Dinah Shore got their first radio break on WNEW. The big band swing era, fortunately, started about the same time as WNEW — Goodman, Dorsey, Miller, etc. — and accelerated the station’s growth. So did all the name vocalists who flourished then, names like Peggy Lee, Rosemary Clooney, Ella Fitzgerald, Bing Crosby, Perry Como, and, of course, Frank and Dinah.

News was not a substantial part of the format in the first years. One of the exceptions was Richard Brooks, a writer with a florid style and a hammy voice, who did a daily commentary program, something like the network news stars. This was the Brooks who later became a top Hollywood writer and director.

Eventually, the water faucet concept of music-on-records programming was matched with a similar idea for news. The networks (and those few Indies that did any news) scheduled their programs, usually 10 or 15 minutes long, at only three of four places in the daily lineup, usually morning, midday and early evening.

WNEW could not compete with the networks with their big news staffs and news stars, like Gabriel Heatter, H. V. Kaltenborn, Raymond Gram Swing, Edward R. Murrow, Lowell Thomas. So Miss Judis abandoned conventional network style news and steered the station into a compelling new news format, which made news easily accessible in short packages, throughout the day and night. It made a good mix with the blocks of music, but yet did not break up the flow in a way to chase the music audience away — a new reason to tune to 1130. News around-the-clock, every hour on the half hour.

It was not rip and read. The news concept worked and attracted new audiences, not just because of its habit-forming, continuous pattern, but also because its quality compared favorably with network news. And it was never stuffy.

A Judis coup brought to the station without cost a unique tieup with the New York Daily News, which set up an entire department of writers and editors who did nothing but prepare the news for WNEW. Staff announcers at WNEW read it.

More than any other radio news of its time, the WNEW/Daily News broadcasts were written for the ear, under the demanding editorship of a man named Carl Warren, who set new standards for writing radio news. Wisely, Judis insisted that the news be straight, isolated from the writing of the newspaper itself, which would sometimes be sensational.

There was one drawback: the news could not be sponsored. The Daily News insisted on this policy, but, in turn, the newspaper did no selling of itself within the news, other than a simple credit that it was written and prepared by the New York Daily News. In a way, this was a plus because those five minute news periods gave listeners almost five minutes of news, not two or three.

Twenty four hours …

WNEW also became one of the first — perhaps the very first — independent station to operate 24 hours a day. Again, in its time not an obvious idea — certainly not when Judis launched The Milkman’s Matinee with the first allnight disc jockey star, Stan Shaw. Opponents of the new format argued that audiences would be so small in the wee hours, that it couldn’t pay any station to stay on the air. But Tudie argued that the cumulative audience would be salable, that in a city like New York with a large potential audience of late-night workers and insomniacs, the figures would add up. The Milkman’s Matinee also made an appealing low cost buy for smaller advertisers, or sponsors who wanted a special audience.

It was said — it might be apocryphal — I. J. Fox, the furrier, one of the early advertisers, bought the Matinee because he believed it was an especially appropriate time to pitch expensive furs — when wives might persuade husbands, or mistresses their lovers, to buy them a fur coat.

The Milkman’s Matinee, Judis figured, also provided another benefit for the station: listeners who tuned to the station at 3 or 4 a.m. would usually leave the set at 1130 when they switched off — a plus for the next day’s morning shows. In any case, the program flourished and was soon copied by many other stations. After a few years, Stan Shaw was replaced by Art Ford, who was built into another disc jockey star.

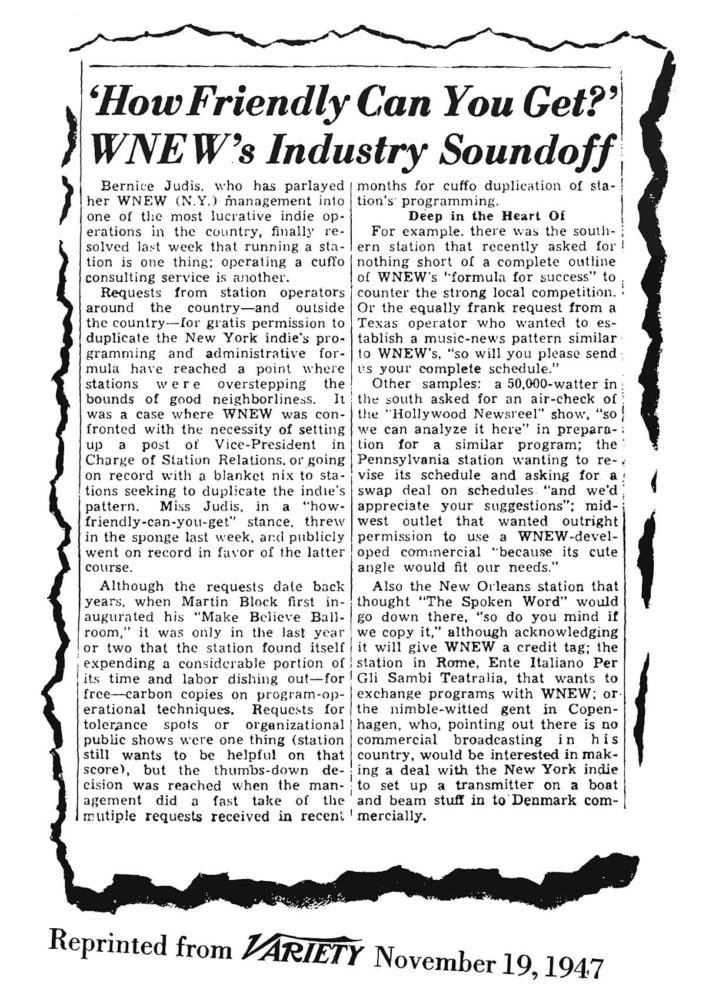

When I went to work for WNEW in 1946 as director of publicity and special events, one of the first assignments Judis gave me was to do something about the flood of requests from other independents all over the country — and even overseas — asking how to program like WNEW; or please, could their manager visit the station himself and see how it was done, and chat with Miss Judis. “We’ve got enough to do running our own station without running a free advice service,” she said to me.

I took a couple of dozen sample letters, including several from Canada and one from Panama, to George Rosen, the radio editor of Variety, and he did a lively piece which quickly cut down the requests for help. I still remember George’s headline: “HOW FRIENDLY CAN YOU GET?”

WNEW’s format and style influenced independent radio from coast-to-coast. Ralph Atlas who made WIND Chicago one of the most successful of the early indies outside of New York, maintained that he did not pattern his station after WNEW, but Judis told me that she knew for a fact that Ralph would come to town, hole up in a hotel room for a couple of days and monitor WNEW. When Bill McGrath, who had been production manager of the station, left to convert WHDH Boston into a music-and-news operation, he borrowed freely from his WNEW experience, and with Miss J.’s permission, even had a daily Boston Ballroom. He also used to call in frequently to get Tudie’s advice and counsel.

Working at WNEW in the ’40s and early ’50s was a postgraduate course in broadcasting and station operation, although the systems and style of the lady would probably not be endorsed by the Harvard School of Business. Miss Judis could be a tough boss, but — to use a good old-fashioned word — inspiring.

While her ways were not orthodox, she was a leader, a manager. She did not believe in budgets, although she kept a wise eye on expenses, income and profit. But she did not go in for formal meetings, memos or management by objective; nor did she use words like goal-oriented or bottom-lime. In her own colorful way, she was imaginative and creative and, above all, intuitive. To explain her talent, you also have to add words like flair and taste.

When we continue in Chapter Four of A Radio Station and its Mistress, Richard Pack will address Tudie’s attention to detail … on and off the air. This article was published in the November 21, 1983 issue of Television/Radio Age, just a few months after Bernice Judis passed away in Florida at age 83.

Next week we’ll review some railroad history and look at a forthcoming major anniversary that’s got the attention of historians and railfans across the land. Then, in early May, we’ll wrap up this series with two remaining chapters of Richard Pack’s story from within the walls of WNEW along with some additional thoughts from yours truly.

Thank you for reading … I do hope you’re finding this worthy of your time. And, yes … I’d love to read your thoughts, comments and even a story you may have!

I am really fascinated by this WNEW history. Thanks so much Marlin!